This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

No one wants to pay more for something than they need to, but how much is the right amount? The purpose of the tender process is to obtain prices from people who have different cost bases and possibly different solutions to offer, so that you can accept the one that is best for you, so long as the offer isn’t unrealistic of course, but how do you determine when you have received an unrealistic offer? This is the great conundrum of the construction procurement process and why people so often default to lowest price as it provides a simple defensible (no personal blame) path to selecting the ‘best’ offer in the clear knowledge that it wouldn’t be offered if it wasn’t realistic. But is that really the case? Let’s look at this from the perspective of someone who has just received an invitation to tender from their client.

Having received a package of documentation and drawings, your client is looking for you to compete on price. In addition to the problems we spoke about in Blog#3 i.e. the weakness of relaying on written information to convey understanding which leads to incorrect assumptions and impressions, after reviewing the information you are aware that;

- Some content is contradictory

- Some appears to be missing

- Some appears to be incorrect

Seeking to clarify issues is time consuming and often not well received by those who put the information together in the first place (and who frequently have a say in tender evaluation). And if you seek to add clarifications within your tender you are generally asked to remove them and confirm it is a compliant bid. You are also aware that you will be expected to take the risk for all the information provided if you secure the work. Furthermore, your experience tells you that, despite assurances that lowest price isn’t the only consideration, you rarely find that you win the work when you have put together what you consider to be the right price.

So what do you do? You daren’t price what you really think your client meant as your competitors will almost certainly not and your price will be too high. So you tread a path between excluding items that are [arguably] missing and allowing sufficient risk to protect you against wrong assumptions, whilst taking a view on current market conditions in an attempt to gauge the right level of profit and overhead to include. The final offer is the best that you can do, but you are none the wiser about whether it is realistic or not until you either win the work or are advised how far off your bid was.

What everyone should realise is the person who does win will probably have reached wrong conclusions, misunderstood some of the requirements and incorrectly missed things out and all of these will unfold as the project progresses, leading to claims and variations that seek to recover these losses as failure to do so could be fatal for the successful bidders organisation. And that’s without having to recover an intentionally low margin designed to secure the work – even though it was known this would be unsupportable at the time of tender – but imperative as turnover enables the retention of critical staff required for long term viability. Some low bidding can also be driven by the tenderer analysing the documentation and ‘discounting’ their price in anticipation of exploiting any loopholes and deficiencies they discover. Even without profiteering, which despite some client’s cynicism, not all tenderers are seeking to pursue, the evidence shows that project outturns will almost universally exceed tender prices. So what can be done to improve this?

Changing the commercial landscape

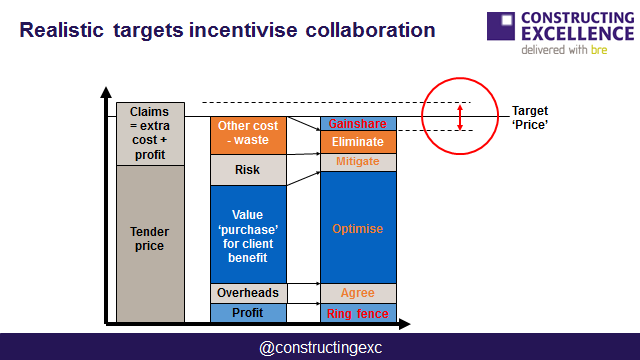

Enter stage left Target Cost Delivery. The purpose of this method is to introduce a realistic cost target for delivery of the outcome. The target being agreed between all contracted parties so that everyone knows what they are trying to achieve. But in seeking to incentivise collaboration and generate value, it goes much further than that as the following image shows.

In the left hand column we see the ‘normal’ appointment position. As we have just seen the tender price is almost always too low having potential technical and commercial errors, risks and commercial opportunities locked into it. The problem is once the process of variations, claims and counterclaims begins, the outturn cost continues to grow as relationships suffer and positions are taken which add cost instead of resolution. Plus the hidden nature of the commercial information means it is all too easy for mistrust to drive the process; as we said in the opening line of this blog, no one wants to be the one paying too much!

The idea of target cost delivery is to change the landscape in which competition takes place by breaking down the price into its primary parts and then adopting different open book strategies for dealing with each of these different elements, which are from bottom to top, Profit, Overhead, Purchased Value, Risk and Other Cost – primarily Waste. By bringing budgetary information into an open and collaborative environment a great deal of the commercial anxiety can be resolved leaving the team to focus on the real task of providing value at a realistic price. Let’s take each of these elements one at a time;

Profit

All companies need to make profit (or build reserve if other organisational models are adopted) without it they will be unable to invest and innovate leading them to wither and die. We have all seen the recent high profile failures where a lack of profit has been a significant contributor to the issues leading to their troubles. So rather than seek to drive profit margins down (as open tendering does) it is far more sensible to pay a realistic level of profit and ring fence this so that the organisations involved are assured of payment.

How much is a realistic level? There are different ways of assessing this, one approach for example, it to work on the basis of the actual profit margin achieved in the last 3 years accounts (with the ability to exclude an abnormal year by agreement). Alternatively a tender process requiring transparency of overhead content and profit levels might be used with an evaluation mechanism which eliminates outliers at both ends against a mean. Others simply state a level of profit to be paid in their invitation documentation. However it is achieved, it must be open so all participants are aware of the arrangements.

Overheads

Just as profit is essential to operations so is overhead. Overhead can cover corporate and project activities and in a fully open book environment it is possible to migrate activity, such as procurement or training for example, between organisations. This can create savings through the removal of duplication or increase the effectiveness of activities by placing them in the hands of those who are ‘more expert’. However this is achieved, overheads or at least the mechanism for paying for them should be agreed in advance so there is no room for misunderstanding at a later date. Not everyone has the same understanding of what constitutes an overhead, so it is essential that there is clarity between delivery costs and overhead inclusions to avoid omission, duplication and future conflict.

Purchased Value

This is the expenditure that is necessary to achieve the outcomes and we will return to it after we have considered the other two elements.

Risk

Through identifying and quantifying the risks, the organisation best suited to resolving them can be identified. By putting risk into the hands of the right party the likelihood that they can be mitigated is greatly enhanced. All organisations including the client will have made provision for risk, by pooling these allocations a risk fund is developed. It is not at all unusual when pooling risk allocation to find multiple parties holding sums for the same risks and so in an open book target cost environment a saving can often be achieved just by reducing this duplication. Not all risks can be mitigated and so some cost will always be realised, but at a much lower level than when undefined and unmanaged risk is pushed down to the organisations that have been appointed through priced tender arrangements. Instead, an open ’whole team’ approach to risk that reaches out to all members of the supply chain is essential, with earliest involvement (see blog#2) being adopted to ensure that the people best placed to understand, hold and manage the risks are available when their influence can be of most value.

Other Cost – Waste

There may be costs which will need to be allocated that do not directly fall under one of the previous elements, but frankly if it adds value it should be incorporated and if it does not it should be eliminated altogether and so this element becomes all about the costs that are included by default, by which we means waste in all its forms. This will be the subject of a separate blog later in the series, but for now it is simple enough to say there is procedural and transactional inefficiency locked into just about everything we do and all parties working together in an open book environment should focus their attention on the elimination of waste at all stages including the design stage.

Core Activity

To return to Purchased Value. What is meant by this is all the costs that needs to be incurred to achieve the agreed outcomes. This means the cost of the people that will undertake the design and delivery including the expertise of suppliers, manufacturers, specialists and subcontractors, as well as the things that need to be purchased to be incorporated into the solution from materials and components, to plant, equipment, fixtures, furniture and finishes. To make this method work it is extremely important to have clarity about what is needed right at the beginning (see blog#1 on meeting the needs), so there is no disagreement later on about whether or not it has been provided, which is why this method works best in an alliancing environment where the key parties (80/20 rule) are selected at the beginning. By having clarity on what is required at the beginning everyone has the opportunity to confirm that the target cost is realistic and this realisation helps to build commitment and ownership.

As does gainshare. Knowing that you are able to achieve gainshare is an incentive to performance. However, the mechanism for quantification and allocation of gainshare needs to be agreed up front, together with any painshare arrangements in case the target cost is not achieved. Gain and pain share should be equitable if they are to incentivise performance; if a participant is prepared to take 25% of the risk on failure, they should also expect to receive 25% of the gain if successful. Those who think it is ok for their organisation to take 75% of the gain whilst their partner takes 75% of the pain; something that is definitely not in the spirit of collaboration, may well find the hoped for realism of open book target cost delivery is fatally undermined. Remember there are many different perspectives about what constitutes optimisation and an inequitable share distribution that acts as a dis-incentive to innovation is more likely to lead to a ‘cheap and dirty’ solution being adopted that barely meets the needs but avoids any risk of overspend. This of course applies whenever incentive arrangements are adopted anywhere throughout the supply chain

However, if realism is adopted, profits ring fenced, overheads agreed and minimised, risks mitigated and wastes eliminated, there should be enough funds released to both deliver optimal if not enhanced value and create sufficient savings to be distributed as gainshare to the participants. And the final outturn, the all up ‘Price’ that is paid, is far more predictable and much more likely to achieve the target level than when it is manged through traditional pricing mechanisms.

Behavioural Changes to Adopt

- Be transparent about what is needed

- Adopt an open and collaborative approach to cost management

- Make sure everyone is clear about what is included in the overhead

- View project risk on a whole project not ‘individual pot’ basis

- Allocate risks to the party best suited to manage them

- Understand that all parties need to make a sustainable level of return

- Share project gains to incentivise innovation

- Seek to eliminate waste to increase value

- Ensure any gain and pain allocation is equitable

- Procure for final project value not lowest entry cost

With thanks to fellow Champion Keith Hayes and Emer Murnaghan (GRAHAM) for their input and improvements.

Kevin Thomas

Chair and Coach of the Collaborative Working Campions of Construction Excellence and Founding Director of Integrated Project Initiatives Ltd, the creators and delivery organisation for the Integrated Project Insurance (IPI) Delivery Model.

This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working