This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

In the process world repetition is king and nowhere more so than for those who manufacture components and products. These are the masters of optimisation and efficiency. In a 24/7 manufacturing plant being able to shave a very small portion off a frequently tiny unit cost can be the difference between profitability and closure. What’s more they have been doing this for a long time and these days only the ‘lean’ can survive.

It was 1799 when Eli Witney introduced interchangeable parts to musket production, undercutting all the competition and kick starting the focus on standardisation, waste elimination and continuous improvement. Over the years this has become established as lean practice, more recently permeating into general awareness through its perhaps best-known form of six sigma with its 7 wastes that famously emerged under the Toyota Production System.

This is a philosophy not a solution and the methods are completely transportable. For example, it sits behind the success of England Rugby winning the world cup in 2003 and the methods of British Cycling where “the aggregation of marginal gains” i.e. searching for small improvements in every action and element, has led to long term world leading performance. As for construction, whilst at GSK R&D, Kevin Thomas applied these principles to the FUSION projects to produce the following and our ninth slide in this series.

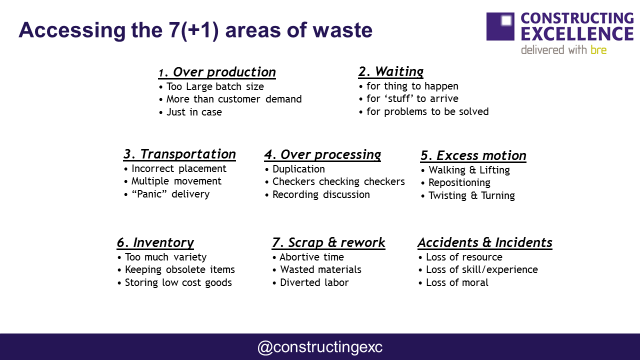

This blog will explore these areas of waste and seek to explain how endemic process and procedural waste is and yet at the same time how in genuinely collaborative environments, superior performance and value can be unlocked through its elimination. Note that by the time six sigma emerged, a focus on elimination of accidents was already imbedded into process thinking, but since this is a fairly recent focus for construction, the +1 waste of accidents and incidents is added.

Lean – Elimination of Waste

As we saw in the latest blog (Working with Cost), if you want to achieve superior value not only do you have to work open book at the root of cost based decision making, you also have to address risk identification and mitigation and crucially eliminate the waste that is endemic in traditional construction. The fragmented operational model means most practitioners are either unable to see or unable to separate and remove these integral wastes which not only accumulate individually but snowball as one inefficient activity locks waste into those that follow.

So let’s keep it simple for now and have a look at each of these wastes one at a time;

Over Production

Essentially this just means making too much stuff when it is not needed. But why would anyone do that? As it turns out there are lots of reasons, the most important being the behaviour of customers. Even in the best planned and executed projects, working with just in time delivery has its risks. For example, delays in transportation, say a rail strike or unexpected snowfall leading to traffic standstill, or material or component supply failure further down the supply chain, can each disrupt flow sufficiently to cause delays on site, meaning a balanced approach to delivery flow needs to be taken. Of course, many projects just aren’t that well planned or organised and any potential for delay is managed out by bringing to site components and materials long before they are needed and at times just in case they may be needed. The intention may well be to send back the unused stock but after it has been mishandled, stored badly or damaged it often can’t go back. Its this kind of behaviour that means the travel straps get knocked of a pack of facing bricks, which slump in a heap and end up being rolled into a site road as hardcore instead of enhancing the facade as intended.

On the other side of the coin, those providing the stuff that is going to be installed are equally attempting to manage the flow whilst trying to guess the requirements of their customers. This can be extremely difficult when low financial confidence turns construction on and off. Those who have invested in expensive production equipment don’t have the luxury of being able to start and stop at will, plus it is a lot more expensive to suddenly respond to a large batch order. So the preference is to keep producing at a steady rate and hope the market will respond. Here construction is no different to say car production where fields of new vehicles await customers that may or may not buy when a new vehicle registration period starts. This is the challenge Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) organisations are facing; how to you turn construction through a factory to benefit from the improved standardisation and quality control etc. if you are unable to match production schedules to a delivery market?

Getting rid of the fragmentation, being open about needs and timelines and working repeatedly with the same supply chain are all methods of reducing the over production headaches and sharing in the cost savings that are available.

Waiting

Every time someone waits for something, time is lost that can never be recovered but still has to be paid for; indeed, as with many of these wastes the inefficiencies described are already locked into the price although this may not be clear to everyone involved. Take the example of carpenters coming to fit doors. If for example, a return visit is usually required because sites aren’t ready for all the doors to be fitted at the same time, that will have increased the cost of operation of the business and been reflected in the quoted price without anyone specifically identifying it as such.

Similarly, customers need to be aware of the impact their procedures can have. A protracted review and approval process that insist on considering trivial items, or which follows an internal timeline rather than being targeted to the delivery programme, will add to this area of waste. And this can easily be compounded by poor information flows or decision-making procedures within the project team.

Transportation

The classic here is setting down in the final place first time to avoid the need to relocate later on. Easier said than done at times as the workfaces and access arrangements can change as a project progresses, but if you don’t stop to consider the logistics from a strategic point of view you can pretty much guarantee the need for double or triple handling with the cost, reallocation of resources and associated loss of activity elsewhere whilst the relocation takes place. There is also the last minute call to the supplier just before close on a Friday saying we need this and that on Monday morning, which apart from the overtime the suppliers puts in to satisfying the order (for free of course – not), it will then arrive on the first available vehicle which might be a 30 tonner that just happens to be heading your way, which incidentally is going to do nothing to help the setting down issue on most sites. At this point it is worth reminding ourselves who is paying for these extra costs. The answer of course being the industries’ clients, since they are the only ones putting cash – everyone else is taking it out.

Over Processing

Over processing is rife in our industry, the fragmentation and separation of design and delivery activity even within the same organisation, adds a level of waste that is simply appalling. We are all aware of the lack of trust that comes with everyone being contracted separately and consequently having differing commercial objectives, but is everyone aware of the implications of that; with each organisation having their own commercial folk protecting their interests and checking that other organisations folk aren’t taking advantage of them? It’s the same with the programme, there is duplication everywhere.

Over processing takes on many guises; too many people checking and needless recording of discussions (in case they lead to an opportunity to claim for something extra or prove that no right to claim exists) for example, or the monthly meeting where every consultant attends to hear the main contractor reading aloud the progress report. The consultant’s determination to oversee the construction activity, and the system of RFI/CVI are further examples that contribute to dragging down the overall construction momentum. And when it comes to supplier engagement, if we don’t have preselected supply chains, we ask for multiple quotations from multiple suppliers growing yet more waste; remember the cost of all this tendering has to be recovered, meaning it is locked into bid price that needs to be paid.

But let’s not get bogged down here with negativity. As we discussed in blog #2, it’s just the imbedded process that creates this environment. Examples of great collaboration and new delivery models show there are plenty of people who are ready and willing to work differently, trust each other, discard duplication and seek to deliver outcomes that will benefit all.

Excess Motion

We are beginning to catch up with the process world at last. The growth in Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) thinking and MMC organisations providing preassembled cassettes or modules is a big step forward. It means we can begin to look at the activities that are undertaken and adjust them to be quicker and slicker, to bring the elements or components to the people instead of the other way around. This, together with improvements to workface access such as those offered by Mobile Elevating Work PlatformS (MWEPS), have improved efficiency and reduced the risk of occupational injury that comes with poorly optimised physical activities. Whilst health and safety may have driven much of this transition, those who have invested are able to demonstrate the cost savings which come from more efficient activities, with fewer defects and better resource utilisation.

Inventory

When you are at home pop into the loft and see if you can find anything you don’t really need anymore? Perhaps things you are hanging on to just in case they might be needed again, even though you really know that much better versions already exists. We all do it and in truth unless we specifically bought a bigger house to accommodate it, we probably aren’t suffering any loss as a result. But in the office or the factory or on site, where every cabin and store is being paid for and the cost of every square metre matters, it’s a different story.

Scrap & Rework

Having to strip something out scrap it and rework the same activity is bad enough, but many forget that it is going to be paid for 3 times over;

- When the work was initially undertaken

- When the work was removed

- When the work was reinstated

Plus there is the loss of time and resources diverted from other workfaces whilst the reworking is ongoing, and the costs of reaching ‘agreement’ that the work was defective and needed to be removed in the first place.

Accidents and Incidents

No one likes to think that there will be an accident or incident that will impact on the people they know or the project they are working on, nor to have to count the cost of it, which is why our industry has rightly devoted so much attention to health, safety and environmental diligence.

Compounded Waste

One of the problems with wastes identification is the amount generated by each event may be tiny, but significant if it occurs daily or regularly when aggregated over a project duration. We are probably all aware that The Egan Report: Rethinking Construction [https://constructingexcellence.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/rethinking_construction_report.pdf] estimated that the waste on an average construction project could be as high as 50%! A ridiculously figure that no business enterprise would tolerate yet manifest in construction project after project.

The truth is it’s the combined effect of these small but influential wastes that compound collectively to produce the 50% suggested by Egan. For example the true waste in over production may start with the cost of labour and materials, but spreads to affect the cost of storage, the tie up of capital, erosion of profits, inflexibility to the finish product once it is made, and the associated environmental costs including unnecessary packaging and pollution. However, rather than seek to assemble and empower a team, many practitioners still see construction as largely a procurement exercise instead of something to do with production. In other words, primarily about negotiating a good deal and placing a main contract – in the case of the client – or a series of subcontracts in the case of a contractor. Ironically, this can result in items being stripped out of bids that are perceived as waste by suppliers because the underlying reasons for their inclusion are omitted or at least unclear, which then adds further waste when the full impact of the omission is appreciated and has to be addressed, often when it causes most disruption.

Rather than being procurement led, the focus needs to be on the formation of an efficient and effective processes that will achieve the end product and add to the end value, in which any activity or process that does not contribute towards creating value in the final product is a waste and should be eliminated. Collaboration amongst the project partners and especially the supply chain is key to the successful elimination of these wastes through a lean approach.

Constructing Excellence has made several visits to study precisely this in Japan and has witnessed how Japanese main contractors would lead and spent time with their subcontractors and component suppliers to discuss ways to simplify and standardise the design over the range of components, in order to expedite on site. By investigating the design in detail and making modification as necessary they would seek to deliver the best quality on site as well as minimise the aforementioned 7(+1) wastes. Poka-Yoke https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poka-yoke featured heavily in the discussions. A subcontractors collective planning meeting would be held on site daily at 1100hr to discuss next day’s production target and the associated logistics of site deliveries, cranage allocation, unloading and best site staging spots for deliveries to facilitate the impending works and minimise secondary handling and excessive motion.

Such meticulous attention to address the waste factors of waiting, transportation, excess motion and inventory at site level meant a smooth flowing of the construction operation i.e. do it as we planned it – also make a large impact on the overall corporate planning, tendering, procurement, cost control and profitability, recruitment and staff deployment.

The traditional UK model inherently provides opportunity for these waste to compound into a significant burden by…….

- Separation between design and construction – leading to inappropriate design

- Uncertain or fragmented responsibility – leading to problems escalating without being resolved

- Contractual and insurance barriers – leading to restriction and delays in rectification, with time lost through seeking legal resolution to technical issues

- Lack of feedback – with no systematic collection and review leading to the repetition of poor performance

- Lack of attention to buildability – leading to redesign and/or reduction in build quality

……. which we should remind ourselves is unnecessarily being paid by the industries’ clients. For example, if we could eliminate 20% of these wastes from the current cost of building 5 schools, we could fund a 6th school at no additional cost.

The industry is not short of innovative ideas and yet paradoxically the industry is slow to change and the same problems appears to perpetuate and repeat project after project. There is definitely movement on a number of fronts, but as has been a theme throughout this series, to reap the rewards requires holistic change, it simply cannot be done alone; effective collaboration is the key and this requires new delivery models if it is ever going to achieve the promise the concepts suggested when the first demonstrations appeared and Constructing the Team was published by Latham in the 90’s. The road to genuine and sustainable improvement is to collectively recognise how easily waste is added unconsciously and how it could similarly be eliminated by examining the construction process under the lens of the 7(+1) wastes with everyone taking small corrective actions to address the issues directly under their scrutiny.

So, If you are wondering how you can improve the efficiency of your organisation, improve the quality of your offerings, beat your competition and deliver better value and more profitable outcomes, you might just want to make a focus on the elimination of waste top of your priorities going forward.

Behavioural Changes to Adopt

- Don’t just look for surplus materials, seek to improve inefficient processes and procedures too.

- Recognise there is waste in just about everything we do and seek to be ‘lean’ by removing it; read “Lean Thinking” by Womak & Jones for more information.

- Understand the value of your input and why it is important to the outcome.

- Consider how your actions could be adding waste to other’s activities.

- Be open to applying thinking from other industries and cultures.

- Make it a habit of looking for the waste in everything you do.

- Challenge yourself. Ask how could we do the next similar piece of work simpler, quicker and easier and what would facilitate that?

- Be aware that you can create waste without even realising it.

- Collaboratively explore what changes can be made; your customers and suppliers are often more able to see the things that are in your blind spot.

- Preselect a supply chain and use it wherever possible.

- Adopt a seamless team approach, using the best skills in the right place, avoiding the need (or perceived need) to man mark.

- Be clear about how your element interfaces and how you can improve the interaction with those who precede or follow; seek to make it better for all of you.

- Make sure you are clear about what the expectations are before you start.

- Always be ready to commence as planned; efficiency starts with having the right materials, the right tools and plant, the right calibre and quantity of people and the right objective.

- At the end of each day, look back and ask, “What could have happened that would have made my job easier?” and strive towards that tomorrow.

Produced in collaboration with Henry Loo. With thanks to Keith Hayes, Ron Edmondson and Odilon Serrano for their input and improvements.

Kevin Thomas

Chair and Coach of the Collaborative Working Champions of Construction Excellence and Founding Director of Integrated Project Initiatives Ltd, the creators and delivery organisation for the Integrated Project Insurance (IPI) Delivery Model.

This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

Comments are closed.