This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

Every report that has investigated performance of the UK construction industry in the last 30 years or so, has concluded pretty much the same thing. Most projects are late or overspent or both. When the 2001 National Audit Office Report (Modernising Construction) studied the performance of government projects over the previous five years, the numbers were 73% over budget and 70% late (statistically giving a staggering probability of a project being on time and under budget of just 8%).

In order for these consistent outcomes to be repeated there must be an underlying cause. It can’t just be bad luck that 92% of projects are failing to hit their primary goals, and that’s without even considering how well the project has met the needs (see the first blog in this series). So what is the problem?

Fully effective teamwork is the key

Since construction is a team-based activity, it’s worth looking at how high performing teams function elsewhere to see if there might be any clues to what’s going on. For this I’m going to look to sport for inspiration. In sport you cannot be successful unless you are a fully effective team, so how do they go about building a team for a new campaign (project)?

The starting point is to assemble the playing squad at the beginning and work to build consensus and ownership of the goals and objectives. This includes taking stock of the skills and capabilities of the team members and determining who is best for which position. They work out how to function as a collective including specific situations and interactions. This might include ‘set pieces’ such as corners, or line outs or power plays (depending on the sport) and will include practicing both within the team and in pre-season or on-tour friendlies, fine tuning so there is no confusion about who is expected to do what and when.

Of course the players are not the only people required, there is also a management team and key backroom staff, coaches, physios and the like, plus the owners or funders who will have a set of expectations (needs) to satisfy. Not that everyone who may be required will be involved right from the start as dieticians, drivers, equipment suppliers and all those who make up the wider support network will join later when needed.

Once the team has performed, they review what they achieved and the mistakes they made (this is expected). Through in depth analysis they seek to understand what happened and adjust and retrain to iron out misunderstandings and systematically optimise performance. Later on it might be necessary to change or add team members – perhaps because different skills are required or new tactics are to be adopted. When they add personnel they work hard to ensure the ethos and methods are shared and understood, before expecting new members to perform effectively.

How does it work in construction?

Let’s contrast this with a construction project. The common wisdom in construction is to appoint designers first and then decide what needs to be done by the delivery partners and broadly speaking how; it seems many are blissfully unaware of the fixity imposed on deliverers by decisions made in the design phase. For our sporting team this is like appointing the backs without the forwards, or attackers with no defenders or just bowlers and not batsmen (let alone specialists like a scrum half, goal or wicket keeper) and then the incumbents deciding how the newcomers should perform, since having played before “we know what they can do”.

Clearly, thinking you understand someone’s capability is not the same as having the skills and experience that comes from operating in that environment, nor does it provide you with greater awareness of new approaches, techniques and technologies over that of the practitioners.

In construction the way we use these design decisions to appoint partners also has a bearing on performance as our next blog on the part played by procurement will explain. And the way we generally expect to go straight into delivery shows we don’t really appreciate the problems this sequential process has created. Not that everyone is ignorant of the issues. “Early involvement” is the common mantra, but ‘earlier’ isn’t the same as ‘earliest’ and whilst it is clearly unreasonable (and unnecessary) to appoint everyone up front, failing to appoint key specialists and suppliers at the same time as the top tiers of the chain means the expertise of significant chunks of the value stream is left wanting.

Of course there are those who do get it and are seeking to make the necessary changes to benefit from the learning. People who understand the importance of establishing relationships based on collaborative behaviours who will draw on a pool of like-minded preferred suppliers. People who will fund workshops and team training and explore issues off-project to determine how best to work together. Even those who will take the time and effort to bring new arrivals up to speed.

Then there are those that see that construction has its own ‘set pieces’ including teams who will prototype, building sample areas to see how everything fits and looks, or (perhaps less regularly) teams who use prototyping as an opportunity to trial working practices to optimise methods, interactions and thus performance. Plenty of people are aware of the benefits of prefabrication and off-site assembly techniques that fall under the title of Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) and there are those who adopt Kaizen style continuous improvement methods which entail collective planning, review and re-planning to tease out waste and inefficiency.

Achieving despite, not because of the process

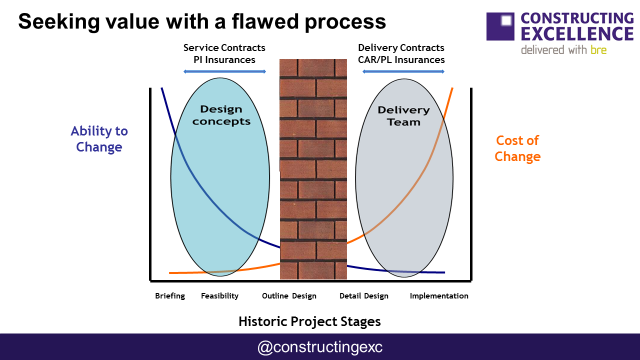

Unfortunately these forward thinking examples tend to be the exception and not the norm and much of the effort is put in to redressing issues which arose from adopting a sequential process in the first place. But this isn’t necessarily anyone’s fault. As a result of separating design and delivery functions, the contracts and insurances that support our industry have become tuned to this method of working and now have become barriers to changing it. As most people are aware from the following well-travelled slide, it is relatively cheap and simple to change your mind right at the beginning and hellishly difficult and expensive to change it at the end. This is why we have the early involvement mantra so we can get those who are most active at the end to participate in solution development up front.

Sadly, there are a few problems with this. Firstly, being involved is not the same as being appointed or contracted. People will participate, nod sagely at suggested solutions but keep their ideas to themselves whist there remains a chance their idea might be ‘stolen’ and used to procure alternative partners. Can you really blame someone, especially given the investment required to set up in the MMC environment, for keeping their intellectual property to themselves before they have an appointment which says they will be paid for sharing and delivering it? Of course there is a flip side which says some people will only offer solutions that maximise their profitability whether or not it is in the best interests of the project, or those who will change key suppliers as soon as they get going and, without any attempt to bring them up to speed, will come back with different solutions based on ignorance or a cynical attempt to create undisclosed savings – what behaviours this process has instilled!

The second problem is a lot further out of most people’s hands. As the slide shows there are different contracts and insurances that are utilised by the different parts of the industry. The design community is normally appointed under service contracts with Professional Indemnity Insurances (PII) as their primary protection. PII is a blame based policy, which means you are required to prove negligence (fault) in order to make a claim. So the design community is driven to create a solution which can be packaged up and thrown over the procurement wall by way of responsibility transfer. On the other side of the wall are the delivery partners who have separate delivery contracts and a different style of insurance (not that PII doesn’t exist here too). That said, the Construction All Risk (CAR) and Third Party Liability (TPL) insurances still seek to apportion blame, so any technical problems which do arise will quickly be subsumed into a legal solution design to determine fault instead of working out how to mitigate the problem.

The blame game sets us apart

It is this understanding which I believe really gets to the difference between sports and construction teams. In sport mistakes are accepted (if not welcomed) as a learning opportunity on route to achieving superior performance. In construction they are something your underwriters and brokers will advise you never to admit to unless a legal ruling says you have to, by which time the problem has all too often grown from something that could have been resolved relatively simply into a team-busting project-breaking monster on the way to being another of the 92% of reported failures.

Oh and just a word for all those clients reading this who believe the insurances are there to protect them in the event of a problem, they are not. PII and CAR/TPL are designed to protect the people who pay for them, not their clients. Furthermore, unless you have checked each and every policy up and down the supply chain, you will not be aware of the different terms, exclusions and excesses that exist in the many different versions of these policies. This could mean you are paying for duplicate cover or you are underinsured or worse still there are holes where no cover exists at all; each of which you are likely to uncover only when a claim is made!

Doing the same thing differently is not the same as doing something different

We have tried over the years to improve this process, with methods such as management contracting, construction management, single and two stage design and construct, but in truth this is just tinkering with the same process and whilst the handover point may have changed we are still looking at a separation of design and delivery functions. It is telling that most contractors have preconstruction and construction sections as design and construct contracts have simply moved much of the divide in-house. So if we are going to improve we are going to need a new process to do it with. Hence the current talk of disruptive change and new models of procurement including IPInitiatives’ new IPI Delivery Model, the first in a generation of what I like to call Insurance Backed Alliancing (IBA) – more about this in blog 5: Achieving Change.

Not that all behaviours from the sporting world should be transferred, there are plenty of examples of dictatorial methods that we could do without, but it is our view that only by adopting a new process that supports full integration and enables genuine collaborative working with partners operating on an equal footing and collectively benefitting from shared incentives, will we be able to emulate the kind of high performance environment that exists in the sporting world.

Behavioural Changes to Adopt

- If you really want different outcomes, be prepared to adopt a genuinely different approach

- Bring people together to achieve a common understanding of goals and objectives

- If you are making decisions on behalf of people who are not party to the decision, you are not working collaboratively

- Your partners can’t suggest improvements or alternatives if you don’t involve them

- Make sure you focus at least as much effort on culture and behaviours as you do on process and procedures

- Early involvement requires early commitment (appointment and payment) if it is to produce value

- If you don’t commit to people don’t expect them to be committed to you

- Trial and prototype to improve products and interactions

- Work off-line to establish how to work with maximum efficiency

- Make sure everyone is clear what needs to be done when and by who

- Seek methods which use collaboration instead of liability-based control mechanisms

- Be clear about the impact of design on potential options

- If you are given the opportunity to influence the outcome don’t waste it by merely feathering your own bed

- Establish how best to collectively solve problems before you find problems that need solving

- Learning together from failings is a more powerful tool for improvement than blame

- Understand the impact separate contracts and insurances have on openness and no blame

With thanks to fellow champions Ron Edmonson (Waterloo), Paul Wilkinson (PWCom) and Mike Reader (Mace) for their input and improvements.

Kevin Thomas

Chair and Coach of the Collaborative Working Campions of Construction Excellence and Founding Director of Integrated Project Initiatives Ltd, the creators and delivery organisation for the Integrated Project Insurance (IPI) Delivery Model.

This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

Comments are closed.