This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

The decisions made in the procurement of projects have the ability to make, or break, collaboration. A procurement process which recognises and focuses on outcomes and which is used as a tool to bring together parties who complement one another and who can, together, deliver more than the sum of their parts, will set a project up for success. A process which treats construction as a commodity, that ends up getting the lowest price, dumping risk down the supply chain and limiting the ability of bidders to innovate, will inevitably set a project off on the wrong footing. Meaning the project is already disadvantaged before its even fully got going.

Poor procurement is not the fault of one party. Procurement teams are more often than not incentivised on the deal in front of them. Many of the CW Champions have experienced first-hand that procurement teams, whether these are client teams or buyers within higher-tier consultants and contractors, are measured on their ability to deliver immediate savings compared to benchmark costs or rates previously paid, and to ensure process, not quality of the final offer, is their focus. But equally, poor behaviours from bidders, gaming rates, capitalising on holes and errors within specifications or simply taking advantage of over-stretched buyers, all create the foundation of an adversarial environment where everyone is put in a position of mistrust.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Procurement principles

Whilst we will be discussing issues and ideas which affect all parties, this blog is primarily looking at the decisions made at the commissioning client end of the procurement lens. Our next blog will look at different procurement approaches and where to apply them more holistically, for now let’s stay mostly at project procurement level.

To avoid the bad, and champion the good, we need to go back to first principles. Before starting any procurement process we must first work out what is wanted; this isn’t a specification, but the outcomes needed from the project. What does it do, how much does it cost to run, how easy is it to adjust and tailor as needs change? Being clear on outcomes enables the supply chain to innovate and bring value from day one.

For all of us, once we know what we want to buy, we’ve got two options. Either you,

(a) Go and find some people who make or do what you want and see what their offers are, or

(b) Implement a process to encourage those who think they make or do what you want to provide you with an offer.

In either scenario you’re going to need to run some form or procurement process, whether that’s a discussion with several potential suppliers or a years long multi-stage OJEU compliant screening, selection and appointment process. The design of that process will ultimately drive the interest, ability to innovate and intentions of bidders to deliver the best value.

With offers from potential suppliers received you’ve got to evaluate. Evaluation is often where procurement becomes a numbers game, and the fear of challenge or not getting the right price can incentivise the wrong behaviours. Evaluation should be open, transparent and designed to reflect the outcomes you desire; thus avoiding a race to the bottom that won’t get you what you need in the long term.

Choosing a winner is the end of procurement but the beginning of the next stages of your project, so taking time to ensure you’ve got the proposition that best meets your circumstances (including – suitability, availability, flexibility, quality, and cost to buy, use, change and dispose of!) is a must. We all need to be confident in our decisions, and if it’s not right, go back a step and re-evaluate or even re-bid. Short term pain of a delay in procurement is nothing compared to the long term pain of working with an adversarial partner for the next few years, or worst getting an end product that doesn’t ultimately reflect your needs.

Challenges

The basic principles of procurement seem simple. Work out what you want, design a process which will help you choose from the market, evaluate and then select.

In reality we need to overcome a few more hurdles before we get this right. If you’re buying a car the process is relatively straight forward, but what about buying a building?

How do you know what you want if you have never had/used/experienced (or even imagined it)? How do you communicate what is it that you want?

Working out what you want, and how you’re going to articulate what you need, is the critical first step in a successful procurement process. More often than not there’s a temptation to revert back to traditional buying principles; describe a product, design a solution and then go out to market to buy it. In this model we appoint designers to design a solution, likely based on a very loose brief, and progressively develop a design proposal before chucking it over the procurement wall to the delivery team (see blog#2 in this series). What happens? Innovation is stifled and the contractor can only really make money through change after the contract has been signed, including initiating change down the tiers of the supply chain, instead of helping you to understand what is possible and beneficial for you and not just them.

So how do we avoid this? Engage the experts you need early, particularly those from the construction supply chain. Select a team based on value they create, not their status in a traditional delivery model hierarchy, it makes all the difference between stifling and encouraging innovation, collaboration and a focus on joint outcomes.

With the experts on board, communicating what you need or want from your building becomes easier. Conversation, workshops and joint exploration become the preferred approach to defining ‘the brief’ and developing your solution. And with the right facilitation, a focus on outcomes, not rigid specifications, frees the team to innovate and deliver better value for your organisation and a more suitable building for your functions and users.

How do you make sure what you ended up with is what you wanted?

Being clear up front about what you need and why (see blog#1 in this series) enables your partners to better screen their offers and proposals and to balance the inevitable development decisions that will arise. Continual validation of your project against this need, whether that’s via design review, independent scrutiny or by simply creating the environment where teams can speak up when things don’t seem right, is key here.

However, to genuinely succeed requires a breaking down of the barriers that mean different parties working on the same project can have different objectives and incentives. Changing the way the team is procured in the first place is a huge step in achieving the necessary alignment and collaborative ownership to ensure what you end up with will work for you.

What happens if you realise you need something else?

Making changes is a common cause of failure in project delivery, unfortunately the construction industry assertion that once their client has agreed to the solution they shouldn’t change a thing completely misses the point. The longevity of a construction project coupled with the speed of advancement of science and technical plus underlying commercial and economic volatility, means that for many clients change during the life of a project is inevitable. However, adopting a procurement process which locks suppliers into a commercial imperative to maximise the opportunity of change as is the case in lowest price appointments, is frankly foolhardy.

Be realistic about where change may occur and seek to identify this during the procurement process. Once appointed recognise that suppliers are locked into a process determined by the procurement strategy and rather than expecting them to accommodate your revised requirements for next to nothing, or worse still attempting to suggest they are merely ‘design development’ and included, will only make matters worse. If you treat your suppliers with respect and help them to find a way to minimise their abortive costs you will also minimise the impact on your outcomes.

There are times when having the courage to hold your hand up, revisit the solution and occasionally even revise appointments is the right action. And recognising that one of the major benefits of appointing the best (not cheapest) people and listening to their advice, sometimes means that although what they are offering doesn’t seem to be what you wanted, it’s exactly what you need!

The ‘Normal’ Process

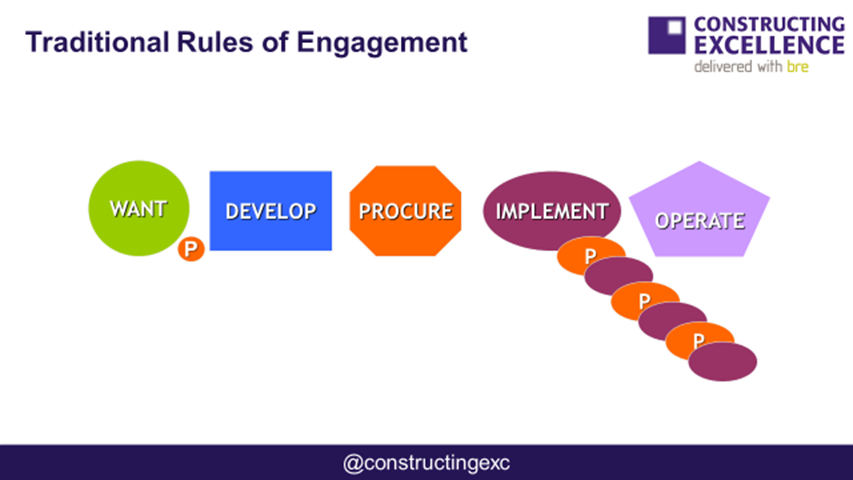

For decades now we have been adopting a sequential process for procuring and delivering construction projects. Broadly speaking this process separates designers and concept development from the contractors, specialist and suppliers who undertake increasing amounts of detail design as well as physical implementation. Over time the amount of design undertaken before the transfer takes place has significantly reduced with the preference for fully pre-designed single stage tendering having given way to a two stage process where some of the design concepts and most if not all of the detail are completed by the implementation team. What has remained consistent is the way separation is maintained by a procurement activity designed to transfer risk and responsibility from the development to the implementation side, as illustrated in the CW Champions slide below.

So how does this process work? At the beginning the client decides what it is that they want. They may have some established advisors who initially help them, but fairly early on they will add other designers as project clarity begins to grow. Most clients believe that progressively designing makes the project cost progressively more certain and so they will seek to limit the design to (affordable) funding stages. Procurement is generally on a time and services basis since we have long ago stopped using fee scales having introduced a ‘competitive edge’ to procurement of designers; by which we mean price based selection has prevailed, more about that shortly.

Unfortunately this means designers have had to offer less and less to be able to win appointments with the consequence that design has become more ‘indicative’. In order to minimise the spend on design without the ‘certainty’ of the contract phase, clients have shortened the appointments by ‘encouraging’ contractors to select the incumbent designers in their project going forward. Under public procurement regulations there are limits placed on the value of contracts including design contracts that can be let without a full compliant (OJEU) tender and some might suggest the truncation of appointments might be influenced by these limits? Whatever the reason it has become common place to appoint designers direct up to a certain RIBA stage and for them to produce the tender documentation and hope (?) that they will be taken on by the contractor to complete the design.

The Communications Challenge

And so to the major procurement activity. The design team have hopefully understood what the client wants and having embedded this in a set of drawing supported by specifications believe this will adequately describes the proposed solution. This information is released to tenderers who are required to respond with an offer based on their understanding of the content.

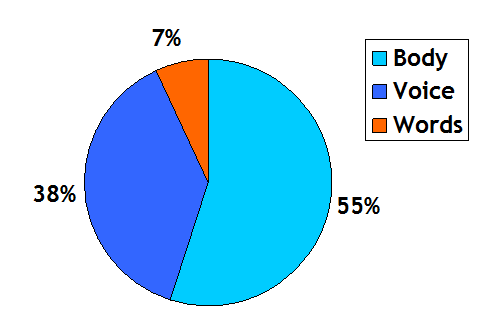

At this point it is worth mentioning Albert Mehrabian’s work on communication. Albert found that we get 7% of our understanding from the words someone speaks to us, 38% from their voice including tone and inflection and the remaining 55% from their body language. Now, although this is for verbal communications it shows us just how important or to put it another way how difficult it is, to convey the full message in words alone. It’s why sarcasm fails so badly in email and why emoji’s have pervaded so much of modern life which has become so reliant on written communication.

Tenders are primarily written information, drawings certainly help as research shows 50% of our brains are wired to receive visual stimulus, but overall understanding the full requirements from specs and drawings alone is likely to lead to misunderstandings, incorrect assumptions and unwanted additions or omissions.

You can ask for clarification, but only on specific points and then only if all parties are given all the responses. This means if you have spotted something significant that might give you a financial advantage in the tender submission you keep it to yourself; rather than allowing it to be flagged up to all your competitors. Most people have also learned that raising too many queries is seen as being critical which isn’t a great thing to be seen to be doing by those subsequently evaluating your submission; especially if they were responsible for creating the information in the first place.

Of course we do know about Albert’s communications gap so we add an interview process to improve evaluation, but given the points just raised this is primarily a sales pitch rather than a meaningful exploration of ideas. And even when it is meaningful, we often fail to differentiate it properly in the tender evaluation.

Putting Price in its Place

Most organisations have a quality price evaluation procedure which is intended to ensure that cheapest price is not the overriding factor. However, even if you have an 80% quality and 20% price evaluation method, you can still end up inadvertently operating lowest price tendering, so how does that work?

Quality evaluation is usually undertaken by different people to the price evaluation and often with quite different philosophies. If you have selected good potential partners you frequently find that differentiation in quality scores can be very low and yet the pricing evaluation mechanism can be quite draconian in nature. A mechanism which awards the lowest price with a 100 out of 100 and everyone else with a prorate score based on the difference can turn 30’s and 40’s out, whilst the quality scores may only vary by 10 or 20 marks across the whole assessment. Suddenly the price scores makes all the difference, especially if there are added benefits which score a little for quality but are heavily penalised in the price evaluation as they increase the overhead, such as training large numbers of apprentices compared to other suppliers for example.

And if this mechanism does slip back into favouring the cheapest price then it’s a return to the days when those who made the biggest mistakes, let alone least understood the objectives, are the winners – until they later work out what they have missed out of course!

Having successfully navigated this procurement hurdle, the selected contractors will be much the wiser to its failings. Why then do they generally apply the same approach to selecting their subcontractors and suppliers? Until you get down the chain to manufacturers that is, when you find that they have a business model locked in to an established supply chain which relies on mutual benefit not lowest price to operate effectively.

We should briefly return to the involvement of designers post responsibility transfer. Before the procurement stage they were working for the client and seeking to provide the best outcomes they could to meet their client’s requirements. Following transfer and if they end up appointed by the selected contractor, they may well find that this objective is at odds with the needs of their new client to make the project economics work, especially if it becomes obvious that errors have been made when tendering. They may also find that their new client is less than sympathetic to any difficulties which emerge in implementing the concepts they have now reacquired ownership of.

What to do going forward

If you focus on procuring for value, not price you’re going the right way. If you work on bringing the right partners on board early, not the partners the organisational chart says you usually need, then you’re one step further. If you embed collaboration, trust and responsibility into your procurement process, you’re onto a winner.

Procurement is a critical step in building a successful collaborative team and delivering a successful project.

Henry Ford once said, “Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.” All three of these things rely on how we procure.

Behavioural Changes to Adopt

- Focus on desired outcomes.

- Incentivise buyers to appoint on value not price.

- Ensure your tenders clearly describe your needs.

- Find ways of augmenting written information to better convey your purpose and objectives.

- Scrutinise the scoring strategy/mechanism to make sure it reflects your intentions.

- Recognise that seeking cheapest price will force your suppliers to respond tactically, exploiting problems and change.

- Be transparent about your selection and appointment process.

- Understand that sequential appointments are more likely to undermine ownership and commitment than achieve certainty.

- Work with manufacturers to understand what an established supply chain should be.

- Recognise that being transferred from client to contractor is challenging for the designers.

- Work out how to align your suppliers with your objectives.

- Consider how you might select individually but still build a team.

Produced in collaboration with Mike Reader (Mace). With thanks to Ron Edmondson (Waterloo) and Odilon Serrano (Mott McDonald) for their input and improvements.

Kevin Thomas

Chair and Coach of the Collaborative Working Campions of Construction Excellence and Founding Director of Integrated Project Initiatives Ltd, the creators and delivery organisation for the Integrated Project Insurance (IPI) Delivery Model.

This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

Comments are closed.