This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

What is the purpose of the construction industry? Assuming of course you can actually separate construction from property and property from functional performance? Is construction there to just satisfy the desires of the commissioning customer or perhaps the customers customers/stakeholders, or is it to provide the overarching infrastructure and facilities in which we all live, work and play? Is there actually any difference in these objectives and how do you make sure that optimal performance can be attained in achieving them?

Let’s start by looking at the automotive industry which is often spoken about as an exemplar that construction can learn from, and rightly so. Understanding the way automotive has streamlined its offering by reducing the amount of bespoke elements whilst dramatically improving the quality, reliability and safety of its products has led to step changes in the construction process. The ongoing transformations in relation to supply chain involvement, integrated design (BIM/Digital) and the growth of Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) including pre-assembly of components and off site manufacturing of major elements, have all been influenced by automotive style thinking.

But the analogy is often overstretched and key points confused. A car is a commodity that is highly specified and regulated by its manufacturers with choices being limited to a menu of tightly controlled “options” (type of fuel, engine size, body colour etc.). In contrast the construction industry is literally capable of providing almost anything the customer requires so long as there is the time and funding to pay for it; this is a long way from being a commodity and yet commodity purchasing methods are widely applied to construction procurement. More about that in a later blog.

By talking about a car in the first place we have already leapt a whole series of important decisions. Why do we need a car? What are the drivers (excuse the pun) which have led to this decision? Let’s go back to the start and follow this through.

“Customer is king”, “buyer beware” are the traditional mantra. This means it’s up to the customer to work out what they want and for industry to provide it for them. It presupposes that the customer knows more about their business or service or activity than construction does and therefore the customer will be more capable of defining what type of infrastructure or facility is required. Whilst the former is most certainly the case the latter is more often not, especially where buildings are concerned. Living and working in a building makes you no more knowledgeable about the best way to design and build one than exercising and eating healthily makes you capable of diagnosing and performing surgery if something goes wrong with your body.

In truth most customers know this and so they employ a design team to help them to develop the solution before going to the market place to get the solution delivered, more about the flaws in this arrangement in a moment.

Back to the point, we have once again skipped the key stage by mentioning the solution. What happened to understanding the problem? Well surely that is what the customer does before moving forward with a construction project? Partly yes, but unfortunately this process is hampered by two problems. Firstly most people are task oriented, with the ones being most successful at getting things done being at the top end of the scale, this means we have a tendency to look for a solution that we can get on with rather than ‘getting bogged down’ in analysis. Secondly and perhaps more importantly, our understanding of what is possible is limited to our experiences – we don’t know what we don’t know – which means people will propose a solution that has been adopted before (even if it failed last time; again content for a later blog). Plus we need to remind ourselves that there are new ideas, processes and technologies arising all the time and the right solution today may be significantly different from the right solution yesterday. Furthermore this knowledge is distributed throughout the players in the industry, not merely vested in design consultants, which is one of the key reasons the traditional sequential process is flawed.

This means it’s easy to fall into the trap of assuming the problem has been analysed and adopting a solution that is actually inappropriate as the following case study illustrates.

A pharmaceutical customer was looking for a new building for 50 people near its west London headquarters. When asked why a new building was needed the answer was as follows. “A new drug has just been licenced and we need to get it to market. We need 15 people to begin the sales campaign straight away and in 18 months or so this will need to grow to 30 people. We can’t fit them into our current offices and we have looked everywhere on the campus and there is no spare capacity, so we will need to go off site. If we go off site we will need support staff of 10 or so, but it would be madness not to provide some spare capacity so that’s why we should build for 50”.

That seems to be a reasoned and well considered statement of a problem which requires a build solution to resolve it, however, once it is realised that the need is not a building but office space an alternative solution emerged. Offices were leased from a nearby workspace solution provider for the 15 immediate employees. Over the next year the entire department was moved to the same location and the largely cellular offices in the exiting accommodation converted to mostly open plan. This increased the capacity of the home accommodation so that the whole department including the additional 30 could return to the campus. The new building was never built and the strategy was repeated through the campus dramatically increasing the holding capacity and future proofing the campus.

It is this kind of evaluation which has led to stage zero being added to the updated RIBA process (we will return to process in a later blog) and to the new models of procurement focusing on the “Strategic Brief” as the starting point for project development. Quite simply both are saying identify the customers need /problem to be solved before seeking to identify what the solution should to be. Back to our car analogy. What is the problem that leads to the purchase of a new car? Is it the need to travel from one place to another, if so where from and to? Is it people or other stuff that needs to be moved? How many and what type and size? How often? Or is it for convenience, comfort or image? Are we just following convention? When you start to think this way you begin to realise the vast range of potential outcomes and how important it is to focus on the right ones.

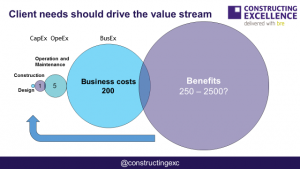

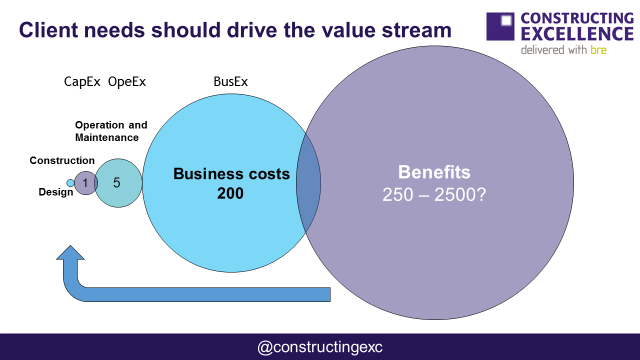

So far we have only talked about the upfront purchase i.e. the capital investment, but one of our key slides reminds us that capital is just one element of the value stream. Below is the much talked about 1:5:200 rule. This states that for every £1 spent on the capital expense (CapEx) of an investment, £5 is spent operating and maintaining the usefulness of the investment (OpEx), whilst a massive £200 is spent on the cost of use (BusEx) i.e. the people, processes and products/services that the facility was designed to provide or support.

We have added a ‘benefit bubble’ to illustrate that there is no point in doing any of this if there isn’t some form of benefit which exceeds the cost of undertaking the activity, even if this is sometimes difficult to quantify, like the improvement in education of children following the delivery of a new school for example. It is these benefits which ultimately define the need and drive the ‘gearing’ of the ratio. We must also of course acknowledge that there is much debate about the published 1:5:200 ratio, however, we are not aware that there is fundamental disagreement that it should be the benefits i.e. the outcomes which should drive the needs, even though they are not included in the original ratio!

The required benefits should pull the process forward informing rather than being pushed along by capital decisions and certainly not, as is too often the case, allowing a separate design process to dictate what is undertaken without the involvement of the delivery side and not appropriately focused on the customers’ required outcomes i.e. their needs. To go back to our automotive analogy what we need is front wheel not rear wheel drive!

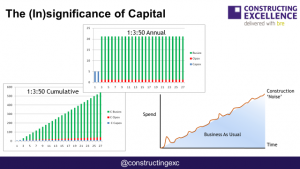

The model also unlocks an important truth which the construction industry needs to understand about its customers. Unless infrastructure or property is an integral part of the business proposition, which is not the norm, most customers are not greatly interested in capital expenditure. Whilst they might push to minimise the extent of capital spend, predictability of expenditure is generally far more important to customers once the amount has been agreed. In the following illustration, the significance of a £10m capital spend (in blue) over 2 years is shown both annualised and cumulatively against OpEx (red) and BusEx (green). This shows how insignificant capital is in pure monetary terms alone; note this is based on 1:3:50 to help those who dispute the ratio to see that it is the orders of magnitude which matter not the actual values.

This unlocks a sobering message for construction professionals. Whilst many customers may have staff who are dedicated to the process of overseeing capital expenditure, when it comes to the impact of these investments construction is just background ‘noise’ and a construction project is a nuisance which gets in the way of the day to day operation of the organisation, diverting resources and disrupting activity. Once you understand this you understand that it is a lack of perceived importance not capability that means customers don’t spend the necessary time on understand their problem enough upfront to provide clarity of requirements including which activities are changeable and likely to require a different approach during the life of the project. In addition and largely because customers spend most of their time and money procuring consumables and equipment, they will often apply the same thinking when a construction project comes along and then criticise the industry for delivering projects late and overspent without appreciating the pivotal impact adopting an inappropriate procurement method plays.

BUT through knowing this and acting on it to ensure enough time and effort is taken to understand the customer needs for the particular investment concerned, the construction industry can excel in providing outcomes which genuinely enhance customers own performance with significantly greater predictability of time and spend. Thus satisfying customer needs and expectations, improving the profile of the construction industry and enhancing the value of the infrastructure and facilities required to enable society to work for us all.

Behavioural Changes to Adopt:

- Explain what is required and why

- Involve other early enough for them to be able to make suggestions

- Be open to alternatives

- Accept challenge as a sign others are trying to do what is best for project

- Learn how to question and challenge in a supportive way

- Be sure you are clear why something is required – if not ask until you are

- Be prepared to offer alternatives

About the author, Kevin Thomas

Chair and Coach of the Collaborative Working Champions of Constructing Excellence and Founding Director of Integrated Project Initiatives Ltd, the creators and delivery organisation for the Integrated Project Insurance (IPI) Delivery Model.

This blog is part of the Collaborative Working Champions series of ten blogs on Modern Collaborative Working

Comments are closed.